The Origin of Student Housing in Postwar Japan Learning Illuminated by One Priest

Today, Sophia University operates three dormitories: Soshigaya International House, Arrupe International Residence, and Edagawa Dormitory. These communities bring together students from Japan and around the world, regardless of their background, year, or major, to live, learn, and grow together.

Let us explore the evolution of our student housing. While maintaining its fundamental purpose, it has transformed in form to continue meeting students’ needs. It began with a single priest addressing the hardships of the postwar era.

1.Bosch Town Rescues Students in Distress

On October 25, 1945, classes resumed amid postwar chaos. While some demobilized students were able to resume their education in uniform, many faced challenges such as housing and food shortages, which led to the suspension of their studies.

The second issue of the Sophia University Newspaper (a student-published paper) reported on the situation at the time as follows:

“The cry of ‘Do something about lodging!’ troubles the Student Welfare Office staff practically every day. Even when lodging is finally found, landlords demand excessively high sums of rice beyond the allocated government supplies or charge 100 yen per month for a six-tatami-mat room with no meals—an amount that is unaffordable for students and only feasible for wealthy war profiteers. With 30% of absences due to housing shortages, this is a major problem. Not only war victims, but also struggling students, must have access to vacant mansions that are opened promptly.”

To respond to the students’ urgent pleas, the university decided to build a student dormitory. Leading this effort was Father Franz Bosch, who was in charge of student affairs at the time. In 1945, the year the war ended, he established a boarding house in Kichijoji that could accommodate about 50 people. However, due to various inconveniences, such as its distance from the university, the university purchased surplus U.S. military barracks (known as “Kamaboko Houses”) and relocated them onto campus. This marked the birth of the student dormitory. There were 12 Kamaboko Houses in total. Five were used as dormitories, one served as a meeting hall for students, and the rest were used for faculty housing and offices for the Sophia Alumni Association.

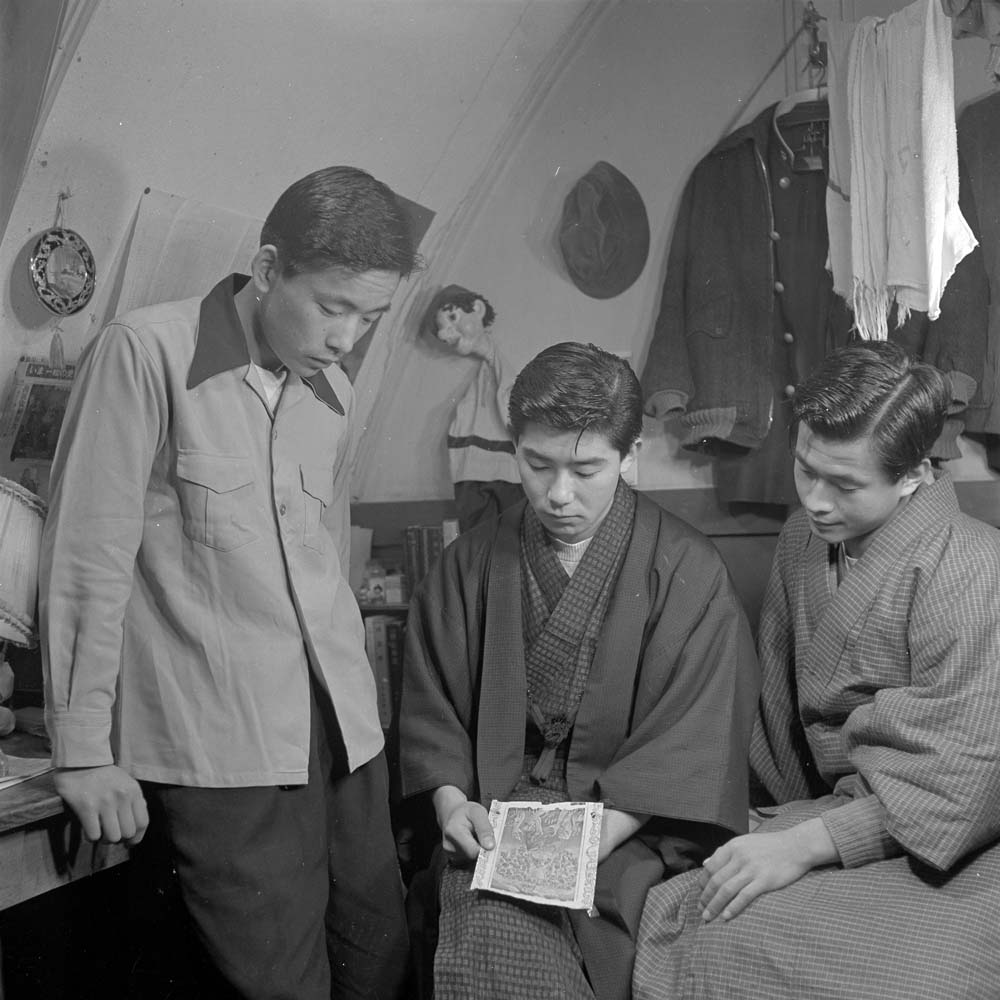

The moving-in ceremony took place on April 20, 1948. Each building housed 16 residents, for a total of 80 people. The dormitory was named Bosch Town after its administrator, Father Bosch. Until a new dormitory was built in 1957, residents lived in this dormitory alongside Jesuit priests who served as the supervisors.

2.Bosch Town Operations and Student Life

Bosch Town was a self-governing dormitory with strict rules. Residents rose at 6:30 a.m. and ate breakfast in the basement dining hall of Building 1. Due to a nationwide food shortage in Japan at the time, the “Sophia University Student Dormitory 30th Anniversary Commemorative Book” (hereafter “Student Dormitory 30-Year Book”) records that: “Breakfast was a roll, and lunch was rice porridge with sweet potatoes and vegetables, with a small amount of rice floating in a bowl filled with broth. Udon noodles were the regular evening meal.” Bath facilities were shared with St. Aloysius Residence, another dormitory in use since the university’s founding. Study hours ran from 7:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m., with lights out at 11:00 p.m. Weekly hiking trips, bimonthly discussion meetings, and sports activities such as volleyball, table tennis, and baseball were also held.

In 1957, the Bosch Town residents, along with the St. Aloysius residents, moved to the newly established student residences within the Sophia Kaikan. Subsequently, Bosch Town became known as the “Q Building” (Quonset House) and was used as a lecture hall with a capacity of 50 students per building. In 1962, it became a clubhouse for students. After Building 5 was constructed as the new clubhouse, Bosch Town completed its mission and was demolished in 1967.

3.Father Franz Bosch

Father Bosch played a central role in the construction of the postwar student residence. He was strict about the rules, but he deeply loved and supported his students. They affectionately called him “Oyaji” (Japanese for “Dad”) and looked up to him. Father Klaus Luhmer, a fellow German and former Chancellor of Sophia University, said:

“The young people of Japan, especially those after the war, were often betrayed, misguided, criticized, and ridiculed. They were seeking someone who would understand them, address their troubles and concerns, ponder their questions alongside them, and provide them with comfort and hope. And precisely because Father Bosch was such a person, his words resonated so profoundly.”

It is said that on Father Bosch’s desk lay a piece of paper bearing the words of the German poet Hölderlin: “When love dies, God also departs.” Father Bosch tirelessly worked to save students from financial hardship and loved them unconditionally. He passed away suddenly from a heart attack on November 28, 1958, the year after the long-awaited student housing was established within Sophia Kaikan (*). He was 48 years old.

The bust, built by those who cherished Father Bosch, stood for many years in front of the Sophia Kaikan student dormitory. It now resides in the courtyard of Edagawa Dormitory, quietly watching over the students.

* Sophia Kaikan was demolished in 2006; Building No. 6 (Sophia Tower) now stands on the site.